Using generative AI to unlock HIV

Aug 11, 2023

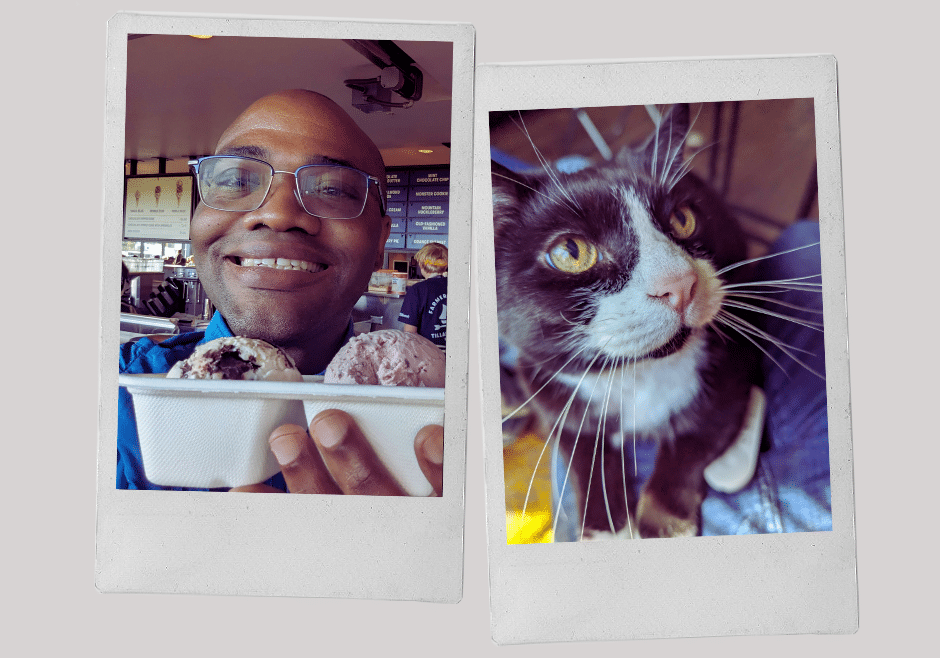

Shaheed Abdulhaqq on the holy grail of HIV research – and the path that brought him full circle in the fight against the virus.

More than 40 years after the AIDS pandemic began, there is no vaccine or cure for HIV. Antiretroviral therapies (ARTs) help many people live longer, healthier lives, but they do not completely eliminate the virus and must be taken for life. Additionally, the cost and inaccessibility of these drugs disproportionately affect millions of people from low-income and marginalized communities.

“HIV is a challenging virus,” says Shaheed Abdulhaqq, Absci Group Leader and HIV researcher. “It mutates quickly and attacks one of the most important types of immune cells in the body,” he says, “so the very thing that fights HIV is under attack.”

A new collaboration between Caltech and Absci aims to change that. A grant to Caltech from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is bringing together state-of-the-art biotech and research expertise in fields like immunology, protein design, and generative AI with the ambitious goal of creating a better, more accessible HIV therapeutic vaccination – one that both treats and protects against infection from multiple HIV-1 strains.

Using generative AI to unlock HIV

As part of the team, Shaheed is eager to apply generative AI to unlock HIV, but the challenge is clear. HIV evades treatment by an ever-changing variety of proteins on its surface, making it impossible so far for researchers to design a drug that can find and target it. Shaheed says the key to defeating HIV may be in the way it infects cells.

When HIV comes in contact with a human CD4+ T cell, he says, “it opens up like a flower.” This exposes the parts of the virus that infect the human immune cell. But unlike the virus surface, this exposed portion is conserved and unchanging, representing a promising drug target. Caltech researchers propose creating a novel HIV therapy that first exposes and then binds to a conserved site on HIV-1. Absci’s role in the project is to design the antibody or antibody-like protein to bind to the exposed region and disable the virus.

“We’re trying to target the virus in a way that no one else has ever done before,” says Shaheed. “If we are successful, this could be the holy grail the HIV field has been seeking for decades.”

Academic roots coming full circle

For Shaheed, this new Gates Foundation project feels like coming full circle. As a research assistant professor at Oregon Health & Science University, Shaheed worked on an HIV project supported by the foundation, and he even won a foundation award for some of his work.

“The Gates Foundation is a wonderful organization, and I don’t know where the field of HIV research would be without it,” Shaheed says.

He began working on HIV as a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, where he was interested in understanding why some people seemed impervious to HIV infection.

“There are many routes to infection —intravenous drug use, sexual intercourse with an HIV partner, or from mother to unborn child. But for whatever reason, some people just don’t become infected. And my research at that stage was really focused on: what is special about these people? Why are they not getting infected?”

Landing in the Pacific Northwest

His graduate work earned him offers in Houston and Portland, though in the end he accepted a postdoc position at Oregon Health & Science University for reasons unrelated to research.

“I remember flying into Houston and looking down at this humongous, sprawling city. There was concrete and buildings everywhere, with maybe a speck of a tree here or there.” He compares that with flying into Portland. “You come in over Mt. Hood, with the Columbia River off to one side, and then the Willamette Valley reveals itself, and it’s just filled with trees. It’s utterly beautiful and breathtaking — I knew I wanted to live here.”

The research was also great. In Jonah Sacha’s lab, Shaheed worked on an HIV vaccine using cytomegalovirus (CMV). The vaccine was somewhat unique in that it didn’t prevent infection, but it induced a strong immune response that ultimately clears HIV completely — akin to some of the super-responders he studied earlier.

“It basically controls the infection and then completely clears it. Very unique. No other vaccine I’ve ever seen works in quite that way.”

Biotech life in the Pacific Northwest

In the five years working on that project, Shaheed had moved up to research assistant professor and had a couple of grants under his belt. Then the pandemic came, and his lab was effectively shut down. It prompted Shaheed to rethink his career.

“I could stay on the academic track,” he says, “which meant a lot of grant writing, and that’s a really hard endeavor and very far away from the research.” Shaheed talked with a lot of grad school friends who went into big pharma and biotech startups. “They seemed happy and passionate about the impacts they were making, and they were a lot closer to clinical impact than I could have been in academia.”

In addition to seeking impactful work, he knew he didn’t want to leave the area. That was about the time that one of his friends mentioned a cool Vancouver biotech firm that was looking for someone with flow cytometry experience. It sounded like a good match for someone like Shaheed — flow cytometry is a key tool in cellular immunology. He met with the Absci team, and when the offer came, Shaheed jumped at it.

“I fell in love with the environment,” he recalls. “I don’t know that we were calling ourselves Unlimiters back then, but the Unlimiter spirit was really strong and alive. I didn’t care about any other interviews. Absci was where I wanted to be.”

Building a wet lab to enable AI

For ten years, flow cytometry was Shaheed’s tool of choice for finding potential HIV vaccines – like finding a needle in a haystack. Now, Absci was looking to Shaheed for ways to improve the use of its proprietary ACE Assay™ technology – developed by Absci scientist Jia Liu – as a high-throughput screening tool for E. coli, its workhorse microbe. Flow cytometry is typically used with large mammalian cells, which are hundreds of times bigger than E. coli. Were there ways to improve the ACE Assay workflow?

“It was a humbling experience,” Shaheed says. “The data we were looking for was in this space that I typically thought of as debris. When studying mammalian cells, you ignore it because it’s fragments, contaminants, and junk you just don’t care about. But with E. coli, all of our signal was in that area.”

Shaheed and the team set about developing the protocols to filter the signal from the noise at a whole new level, including new assays, improving sample preparation, and changes to the instrument itself. It also demanded a more innovative approach, with the team asking itself: What unique features of E. coli can we leverage to use flow cytometry to analyze and assess bacteria?

Shaheed isn’t giving away any secrets, but he says it was great fun — and a privilege — to plow into the problem, mentor the team, and help guide novel research and development of one of Absci’s core technologies – which in effect makes the impossible possible.

Today, Shaheed leads Absci’s ACE Assay team. What the ACE Assay platform can do in the lab is central to what Absci can do with AI. Shaheed says the ACE Assay technology is perfect for screening millions of AI-designed antibodies to determine which ones bind to a target. In addition, all that data about what binds and what doesn’t creates a huge volume of training data for our AI models.

“That enables our models to define a binder that’s even tighter than anything that was in the training set,” Shaheed says.

Believing in the impossible

As the Caltech project gets underway, Shaheed again feels the same sense of awe at the challenge ahead. To be successful, it will demand innovation and collaboration across multiple different teams: AI, Strain Engineering, Biophysics, Protein Engineering, Strain Engineering, Sequencing Development, and ACE Assay Teams.

“It’s a very challenging project,” but Shaheed says that’s not a discouragement. “At Absci, we’re frequently doing things that no one else has ever done before.” This project is no different.

“Absci is a generative AI drug creation company, but we also have a passion for solving really difficult problems to improve the world,” says Shaheed. “It’s a beautiful merger of creating products to help patients and also enjoying the adventure of cutting-edge research. It’s that beautiful synthesis that really makes me appreciate Absci and our work.”